Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania just pioneered a new, easy way to recycle rare earth metals.

That’s good news—because rare earth metals are essentially the building blocks of our modern lives. They are necessary to the production of pretty much every single high-tech gadget on the market—from digital cameras, to tablets, to electric cars. And until now, recyclers have been all but incapable of recovering them. Currently, less than 1% of rare earths are recovered by recycling facilities. Despite the name, though, rare earth metals aren’t exactly rare. While relatively plentiful, they are dispersed in low concentrations, which makes them extremely difficult and dirty to mine.

“To accumulate an appreciable amount of these elements—so named for their low concentrations in the Earth’s crust—we have to dissolve large chunks of natural minerals, a process that involves an elixir of nasty industrial acids and other solvents,” writes Gizmodo’s Maddie Stone. “In doing so, we also extract radioactive elements such as thorium and end up generating tremendous amounts of toxic waste.”

The process is so costly to do in an environmentally responsible way, that we don’t mine many rare earths in the United States anymore (Molycorp’s Mountain Pass Mine in California is the only operational rare earth mining facility left in the US). Instead, most rare earth mining takes place in China.

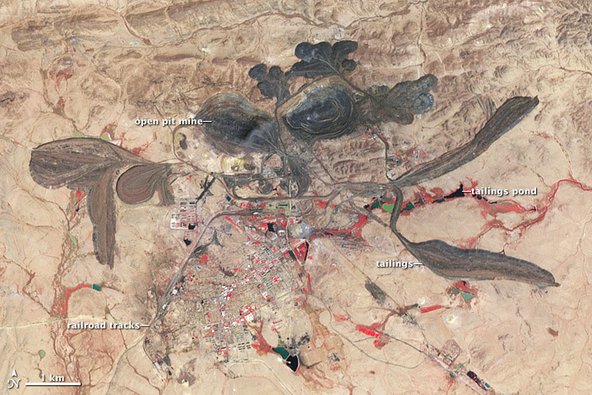

Earlier this year, a report by the BBC’s Tim Maughan shined a light on just how destructive the mining process can be. Maughan visited Baogang Steel and Rare Earth in Baotou, the largest industrial city in Inner Mongolia. According to BBC, the mines outside of Baotou contain as much as 70% of the world’s rare earth reserves. And processing the metals has taken its toll on the local landscape, including a massive tailing pond that Maughan described as a “toxic, nightmarish lake.”

“It’s a truly alien environment, dystopian and horrifying,” said Maughan. “The thought that it is man-made depressed and terrified me, as did the realisation that this was the byproduct not just of the consumer electronics in my pocket, but also green technologies like wind turbines and electric cars that we get so smugly excited about in the West.”

Unfortunately, it’s as difficult to recycle rare earths as it is to mine for them. And the difficulty makes it too costly to be economically feasible for recyclers. So every new consumer electronic and electric car necessitates the mining of new rare earths. Which is why the UPenn researchers could be on to something huge. Specifically, the UPenn report identified a new method that would clear the way for more efficient recycling of two rare earth elements: neodymium and dysprosium.

“Neodymium and dysprosium are often mixed together to create magnets with excellent magnetic and thermal properties. But because different ratios of the two elements are needed for different applications, it would be great if we could tease them apart again after use,” Gizmodo explains.

And that’s exactly what the researchers were able to do in a whole new way. They developed a molecule that lets them dissolve the neodymium into a liquid, leaving the dysprosium behind as a solid. The resulting recycled metals yielded samples that were 95% pure, according to UPenn researcher Justin Bogart. And the new separation process only took about 5 minutes, instead of several weeks—which might go a long way towards making this kind of recycling more viable for recyclers.

So hopefully, in the near future, recycling won’t be quite as rare for rare earth metals anymore.

0 comentários